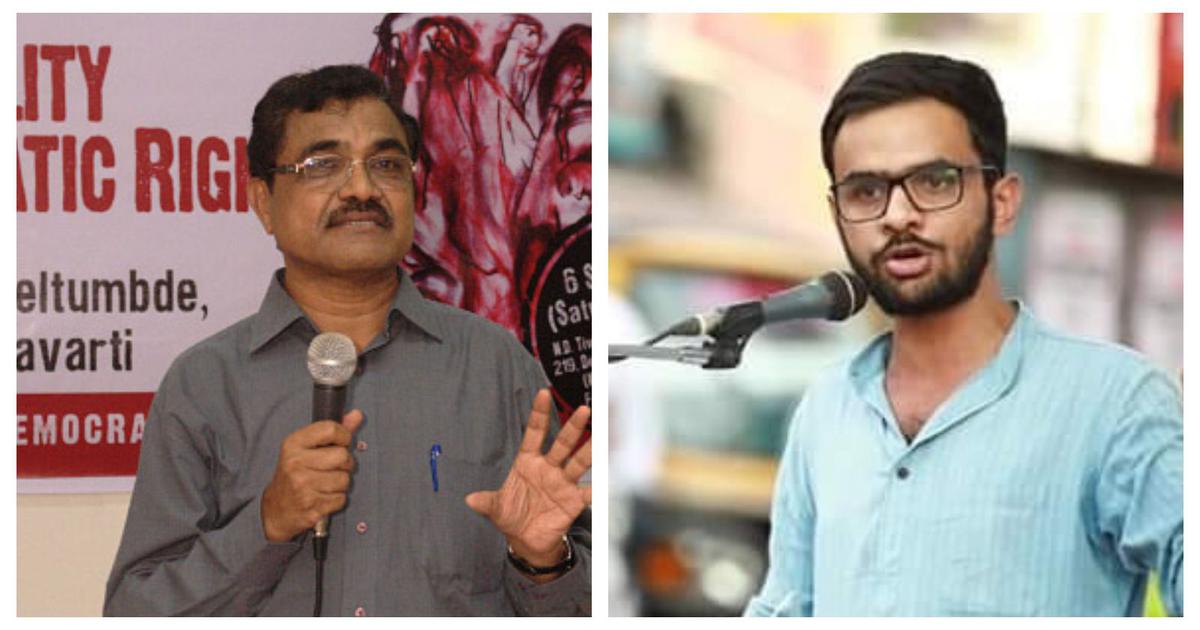

In The Cell and the Soul: A Prison Memoir, Anand Teltumbde notes that incarceration does not only test the body – it also tests whether the mind will refuse to surrender.

That observation sounds a little abstract until one remembers what he endured: months of humiliation, surveillance and the slow discovery that in India’s prisons, time itself is punishment. His reflections are not about one man’s endurance. They are about a republic’s ability to live comfortably with the confinement of some people.

Teltumbde spent 31 months in jail under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act before being released on bail in 2022. His ordeal, like that of many others, exposes a legal order that converts waiting into guilt and procedure into penalty.

The National Crime Records Bureau’s Prison Statistics India 2023 shows that nearly 73.5% of India’s prisoners are undertrials – people not yet convicted of any crime. Behind that abstraction lies a quieter truth: for most who enter the system, justice never arrives; only waiting does.

‘The victim card’

This politics of waiting defines an entire generation of prisoners of conscience. In recent weeks, the Supreme Court has been hearing bail petitions of Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Meeran Haider, Gulfisha Fatima, and Shifa-ur-Rehman – all accused of playing a role in the Delhi riots of 2020 and charged under the same anti-terror law under Teltumbde.

On October 27, the court declined the Delhi Police’s request for more time to respond. By October 31 and November 3, senior lawyers for both sides argued again before the bench. It fixed November 6 for the case to continue. Each date a step forward on paper, a standstill in practice.

This story was originally published in scroll.in. Read the full story here.