By Nidah Kaiser And Tamanna Pankaj

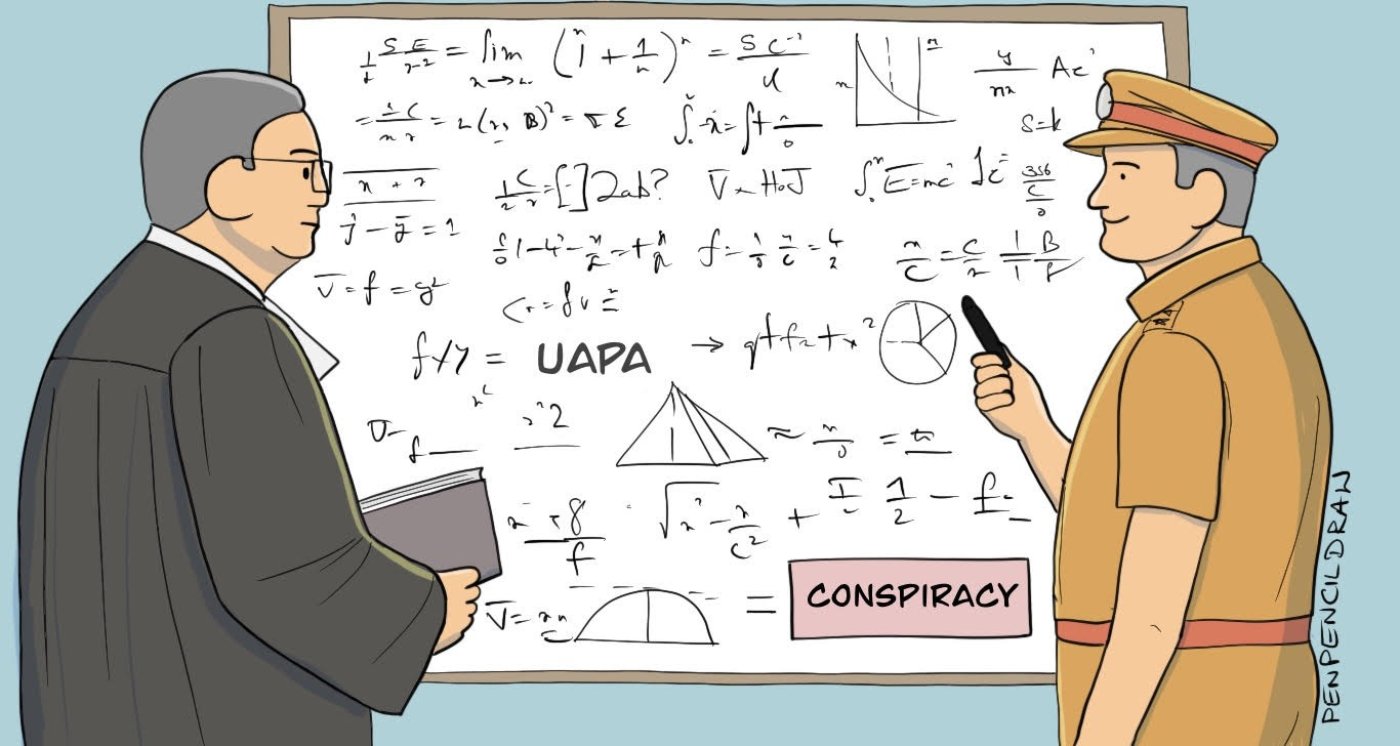

New Delhi: India today jails scores of political activists under a slew of laws, primarily the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), keeping many in custody for years before trial—often only freeing them after bail orders by higher courts.

Take the Bhima Koregaon (BK-16) case, where 16 activists were arrested under UAPA in 2018. As of 2025, 4 of the 16 remain behind bars without bail or trial. Similarly, Kashmiri human-rights defender Khurram Parvez has been detained for nearly four years on UAPA charges.

Even in the high-profile 2020 Delhi riots “larger conspiracy” case, the Delhi High Court refused bail to activists Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam and seven others in September 2025, five years after their arrests.

These are not isolated instances but part of a trend that has developed in the last decade: undertrial detainees in political cases spend half a decade or more in jail before any substantial progress, in defiance of rights conferred by the Constitution.

The union home ministry told Parliament on 2 December 2025 that 10,775 arrests were made under the UAPA between 2019 and 2023, with only 335 convictions—a conviction rate of about 3.1%.

As India marked World Human Rights Day on 10 December, the plight of jailed activists underlined the gap between rights rhetoric and judicial practice.

Bail Only After Higher Courts Intervene

Most of those arrested eventually have won bail in higher courts on strong legal grounds—but only after inordinate delays and extended imprisonments.

This story was originally published in article-14.com. Read the full story here.