By KARAN TRIPATHI

“I hope I get to see her before I die. After all, I’m getting old,” Mahavir Narwal yearned to meet his daughter Natasha while talking to a journalist in October 2020. In another interview, he urged his incarcerated daughter to continue her resistance against injustice. “There is nothing to fear about being jailed,” he said.

On May 09, 2021, Mahavir Narwal succumbed to COVID-19. He died without getting to fulfil his last wish – to have his daughter by his side. All this while, Natasha’s plea for interim bail had been pending before the court.

Jailed For Dissent

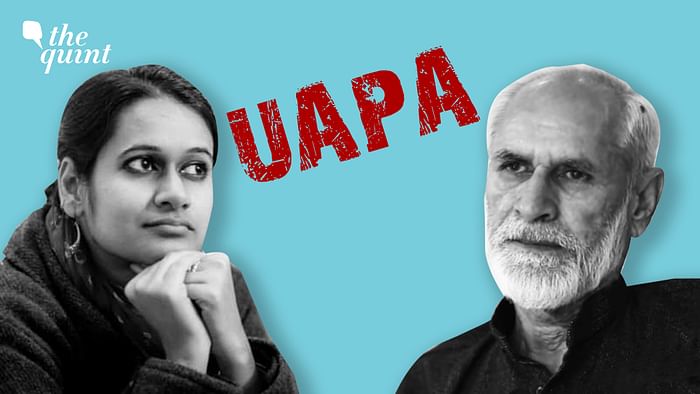

Natasha Narwal has been languishing in Tihar’s Jail’s prison for women for over a year. She’s was charged under the draconian anti-terror law – Unlawful Activities Prevention Act – for allegedly inciting communal riots in Delhi’s northeast district in February 2020.

The State’s only evidence against her was that she allegedly gave an “inflammatory speech” inciting people to take up arms. She is facing multiple cases based on the same evidence. While she was granted bail in one case (FIR No. 50), she was denied release in another (FIR No. 59), despite the evidence against her remaining the same. The only reason for the denial – UAPA.

While granting her bail in FIR No. 50, a judge in Karkardooma’s district court noted that Natasha doesn’t pose any flight risk, and there’s no possibility of her tampering with evidence as all the witnesses in her case are either police officers or protected witnesses.

Further, the court raised serious doubts on the strength of the prosecution’s case against Narwal, poking holes in the only evidence against her.

“… Video shown by the prosecution does show Narwal participating in the ‘unlawful assembly’, but it doesn’t show anything to suggest that she indulged in or incited violence.”

Additional Sessions Judge Amitabh Rawat

When the visual evidence doesn’t support the allegation of inciting violence, what is the case under UAPA even founded upon?

Pressing UAPA against Narwal is an attempt to “otherise” her, to present her as not just the “enemy of the state”, but also the “enemy of the people”. Under this narrative, the state legitimises its violence and degrading treatment towards Narwal. The stringent provisions of UAPA ensure that this legally licensed ‘punishment by process’ of the dissenter continues with negligible scrutiny of human rights.

UAPA: A Licence to Punish Without Proving Guilt

The Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, India’s anti-terror law, which was amended by the present government, has become a primary tool for stifling dissent.

As per data presented before the Parliament by the Union Home Ministry, only 2.2 percent of UAPA cases between 2016-19 ended in conviction. While arrests under the same anti-terror law have substantially increased since 2014.

One of the UAPA’s severely problematic provisions is Section 43-D(5), under which the court can deny bail if it believes that the accusation is prima facie true after relying on the police material.

Section 43-D(5) not only sets a higher standard of assessing “prima facie truth” at such a preliminary stage of the investigation, but also restricts the court’s decision-making to material produced by the police. This gives unfettered powers to the police to produce only that material before the court, which favours its narrative. This means that evidence pointing to other possible narratives, which could go in support of the accused, simply may not appear before the court.

So, the process of arriving at the “prima facie truth” is heavily, and unfairly, skewed against the accused at the bail hearing.

Anushka Singh, a civil rights activist based in Delhi, believes that UAPA not only criminalises the fundamental right to association, it also dilutes the distinction between political dissent and crime, by criminalising dissident voices and acts of dissent.

Singh further claims that UAPA “engenders a culture of political witch-hunts” where selected organisations that question the legitimacy of the state and the ruling classes, find themselves are outlawed and targeted.

Natasha Narwal is one of those dissidents who has been marked as “outlawed” by a law that legitimises the egregious practice of prolonged pre-trial incarceration under the ambiguous, manufactured, and exclusionary ground of “national security”.

Natasha Narwal, a Reformist Not a Terrorist

Even in prison, in a space that by its very design engenders pain, hopelessness, and fear, Natasha Narwal has been a reformer. She is actively engaging with other women inmates to understand their plight of incarceration and how penal institutions end up punishing instead of “reforming” women offenders.

Natasha Narwal, along with her co-accused Devangana Kalita, has been imparting education to the children of incarcerated women. They also moved a plea before the Delhi High Court highlighting how the plight of women prisoners is aggravated by the pandemic, seeking a series of jail reforms.

It was due to their efforts, that the Delhi High Court passed a series of directions to help the women incarcerated in Tihar’s Jail No. 6. The court directed the jail authorities to provide a tele-calling facility to quarantined prisoners, to provide a policy for vaccinating inmates, to make e-mulaqats functional, and assuring adequate legal aid and functional computers and internet in the computer room.

Even as the state continues to punish Natasha, tries to silence her dissent, she seeks reforms and human rights even during her time in jail. And yet, the state continues to portray her as a “terrorist awaiting trial”.

Narwal’s continued incarceration despite her background, behaviour, and beliefs, is a punishment in itself. A punishment that is meted out without proving her guilt, a punishment that stands antithetical to all established principles of criminal justice.

The draconian UAPA and a reticent judiciary has ensured that Narwal continues to remain a “terrorist awaiting trial”, “too dangerous to be released”, and a “threat to national security”. Even though, under law, she is innocent until proven guilty. It is the extra-legal character assassination, smothering of due process, silencing counter-narratives, and fracturing access to justice, that already subjects her to penal punishment.

A State-Controlled Grief

Despite her plea, Narwal was never released to spend time with her ailing father. The only parent she was left with after the demise of her mother a few years ago. On May 10, the Delhi High Court allowed her to be released on interim bail to attend her father’s last rites.

Natasha is “allowed” by the State to finally greet her father, not at home with a smiling face, but at a crematorium with his corpse covered from head to toe in a “leak-proof plastic bag”.

It is not just her continued incarceration, but also her release on interim bail that exposes the insatiable punitive fetish of the State. She was told to give her phone number to two police stations, strictly comply with COVID protocols, submit a personal bond of Rs 50,000, and most disturbingly, to maintain “radio silence” about her case.

The central government, while it did not oppose her interim bail at this stage, asked the court to direct Narwal to not “tweet” or “post anything on social media” about her case or the Delhi riots in general.

Even in unfathomable tragedy, the State’s punitive instincts are trying to orchestrate, restrict, and control Narwal’s grief. Even in temporary freedom, she is incarcerated by the state’s agenda of imaging her as a criminal released under state’s compassion. What she really is, though, is a daughter, a sister, a woman, punished and failed by this country’s oppressive criminal justice system.

This story first appeared on thequint.com