By Felix Pal

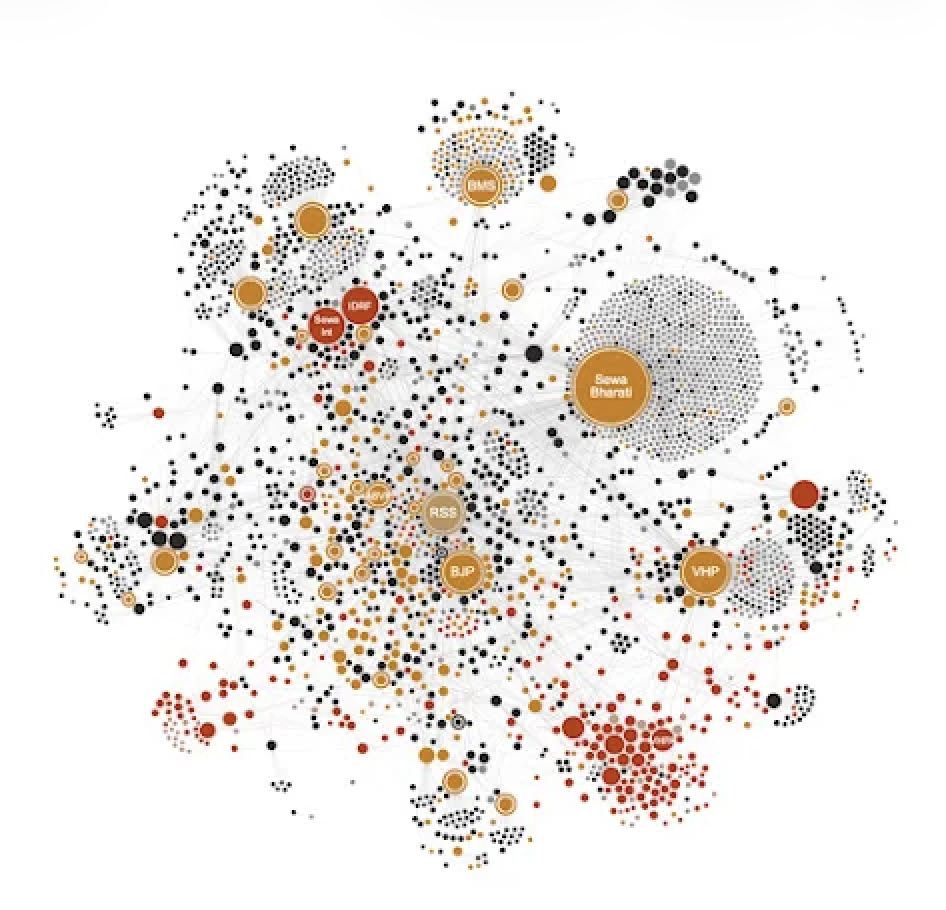

“THE SANGH DOES NOT CONTROL, neither directly nor remotely,” Mohan Bhagwat, the chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, insisted during a conclave in August. The organisational fountainhead of the Hindu Right is celebrating its centenary this year. In a series of public events to mark the milestone, Bhagwat took on the air of an aloof parent, as if eager to distance himself from his children. The RSS is at the centre of a sprawling network of organisations, but Bhagwat claimed that Sangh affiliates “are independent, autonomous and they gradually become self-dependent.” In several of its public materials, too, the RSS repeatedly disavows a relationship with organisational progenies that fall outside the approximately three dozen affiliates it officially acknowledges.

It is, however, common knowledge that the Sangh’s influence extends far beyond this limited circle. Mere days before Bhagwat’s comments, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared, during his Independence Day speech at the Red Fort, that the RSS is the “biggest NGO in the world.” Modi’s statement leveraged the precise ambiguity Bhagwat’s comments sought to obfuscate: the existence of a wide constellation of RSS-linked organisations spread across many sectors of society, whose cumulative reach is central to the Sangh’s power.

Why has the size, shape and nature of this network never been empirically investigated till date? Well, because the Sangh is invested in keeping it that way. The RSS, as has been repeatedly noted, is not registered—not as an NGO, not as a religious trust, nor as any other legal entity. The Caravan’s July cover story, titled “The RSS does not exist,” demonstrated how this lack of traceability on paper allowed it to set up a headquarters in the heart of the national capital without having to disclose its sources of funding, or even who its members are. Most crucially, although the RSS openly works through proxies, it has constantly dodged demands to outline what those proxies are and how it is connected to them.

In fact, in Sangh public materials, one can find a dizzying variety of descriptions of what exactly these organisations are, including within a single text. For example, in Rakesh Sinha’s 2019 book Understanding RSS, these organisations are collectively described, at different points, as “affiliates,” “organs,” “fronts,” or “progeny” that “belong to the RSS.” Ratan Sharda’s RSS 360: Demystifying Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, published a year earlier, also moves fluidly between “affiliate,” “RSS-inspired,” “projects,” “sister organisations,” “allied organisations,” “RSS-related organisations” and “associate organisations” that are “run” by the RSS.

Given this fluid language, it is unsurprising that most research and reporting into the Sangh has been hamstrung by a broad environment of uncertainty and confusion. Because journalists and analysts have, for the most part, been denied meaningful access to the inner workings of the RSS, they have mostly been confined to studying its ideology or its most visible affiliates, such as the Bharatiya Janata Party or the Vishva Hindu Parishad.

This story was originally published in caravanmagazine.in. Read the full story here.